The Skirhem Range

Composing three quarters of Norgas’s southern border, the Skirhem is the longest mountain range in the province: roughly four and a half thousand miles and fifteen thousand feet at its highest point. Due to its sheer scale, the Skirhem range is characterized by myriad microclimates. Travelers attempting to cross through the mountains report seeing strange clouded valleys and frozen pockets hidden low and away within the vastness of the range and have heard howling winds echoing throughout the range.

The northern face is predominantly rock and coniferous forest. Bordering The World’s Grave, it is characterized by strong winds, frigid temperatures, and high precipitation. The trails here wind through patches of dense forest, steep rocky cliffs, and large boulders that must be scaled in order to pass. These trails are inaccessible by vehicle and must be traveled by foot. Most border crossings are made as the range tapers off near the southern end of Viremar or by sea on the eastern border.

The Skirhem is one of two ranges within Norgas. Although it’s more hospitable, temperatures drop precipitously in the winter. The range’s climate remains fair in the summer and it is home to numerous hamlets. Chief among them are Agrassh, at the midway point between Viremar and Haevmer, the dominant eastern port city that stretches up into the range.

The Skirhem makes up most of the southern border to the province, stretching from the easternmost point forty five hundred miles across to Viremar, where it tapers off into the flats of the western border.

History

The Skirhem range is revered in almost every region of Norgas. Most ancestry within Norgas dates back to the Skirhem crossing before the province was settled.

Stories and tales of Icasz and his followers, who were the first to cross the range into Norgas are ubiquitous from Haevermer to the Icaszs and are passed down to young ones so their ancestors' trials will never be forgotten.

As mentioned, Icasz and his followers were the first to cross the great Skirhem into Norgas. Although there are few surviving records of the crossing, scholars estimated that the migration lasted for five to ten years. Over the course of these years, small towns were built along the mountain paths and forested slopes spread out along the main path cut through the range. Icasz and his followers scattered throughout the province, taking with them stories and practices from the crossing.

Outside of folklore and ancestral tales, the Skirhem has always acted as a stalwart wall between Norgas and the rest of the continent, rendering Norgas a backwater at best with little connection to the south. Trade is instead funneled into Viremar at a western inlet where the mountains taper. This long and expensive journey around four thousand miles of mountains acts as a deterrent to those hoping to trade with Norgas. It also keeps those within Norgas from trading outside of the province.

Curiously, folklore from the Skirhem is intertwined with tales of the Hunter. In particular, depictions of the Skirhem are always drawn alongside the great cat. Within the stories and fiction regarding the Skirhem, The Hunter always plays the role of guardian or predator while the range itself is often described and depicted as a great wall or impassable cliffside. As far as anyone can tell, The Hunter has always lived within the range so by itself, this connection isn’t all that strange. However, throughout the centuries since the first crossing, these stories have remained almost identical to their first telling’s. Such consistency over such a long period of time has led historians and even scholars of the Archons to theorize that the range and The Hunter are connected either biologically or otherwise. These theories are hotly disputed by the followers of Icasz who believe the great cat to be some sort of divine soul or being.

Environments Along the Skirhem

Eastern Skirhem

With its staggering length, the Skirhem has a broad diversity of different climates. The eastern end is humid and wet due to its proximity to the coast. Tall grasses sprout a foot and a half off the ground, blanketing the foothills down into the coast. Farther up, the range is host to great cloud forests wrapping part of the northern face and most of the eastern mountains in heavy fog and low cloud cover. The marine layer is a constant. Like liquid, it seeps into valleys deeper in the range, pooling in crevices and pockets. The trees here are not as thick and hearty as the forests farther inland. Instead, the vegetation is less wooded. Trees are far thinner and have much larger leaves. The forests remain very dense, with an abundance of different mosses, ferns and other leafy plants, and even beautiful blossoms at the low end of the forest. The trees are abundant, crowding the ground with their roots and the sky with their branches, impossibly intertwined around their neighbors to create a thick canopy. The most abundant vegetation by far is the moss and lichen that grow on almost everything within the forest. They cover the trunks of trees and hang from every branch. They swallow up roots and rocks on the forest floor, making the ground treacherous and slippery. Under the sea of fauna, the ground is mostly mud and rocks, making traveling at speed treacherous.

“The marine layer is a constant. Like liquid, it seeps into valleys deeper in the range, pooling in crevices and pockets.”

Central Skirhem

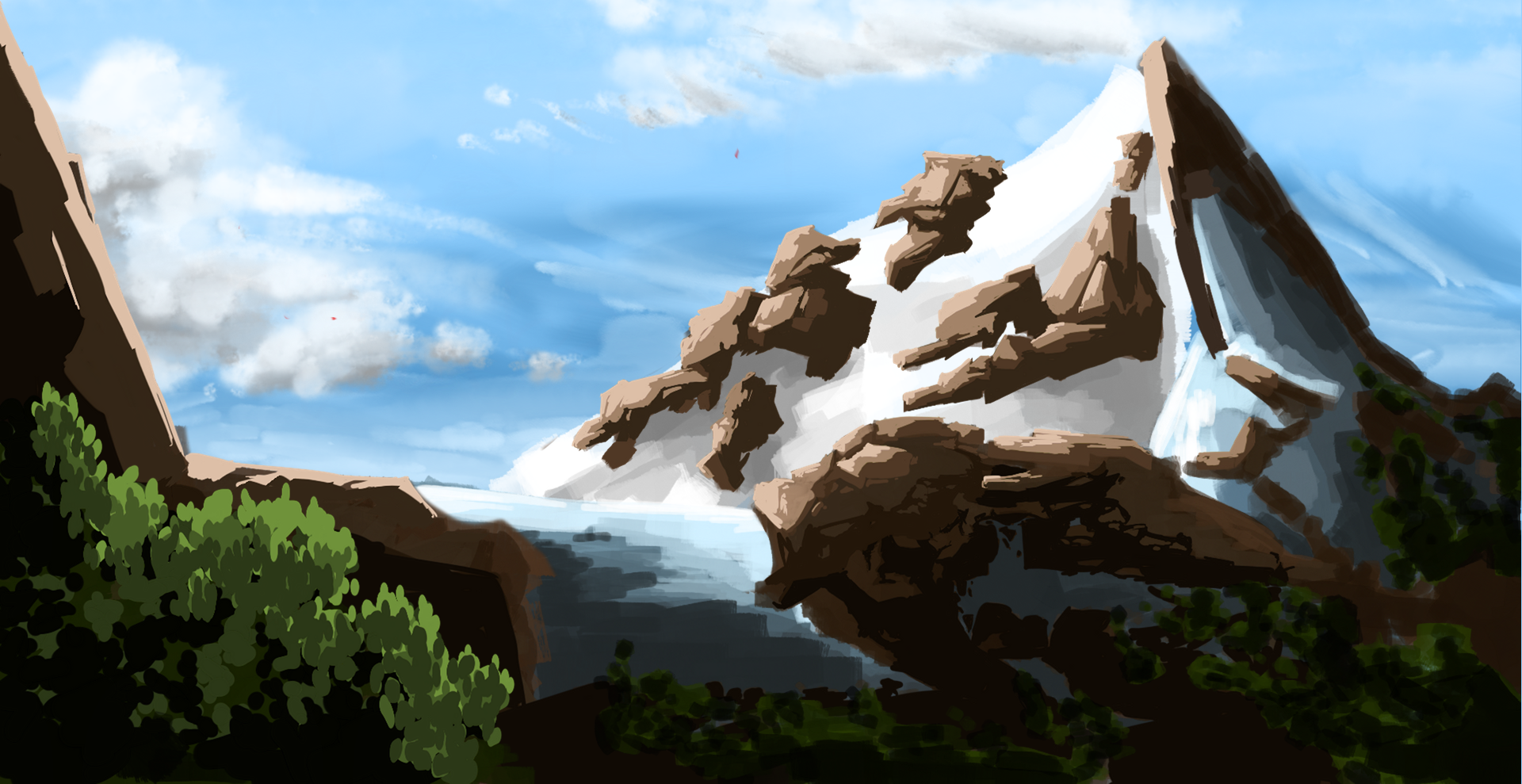

Farther from the coast, the weather becomes dryer. The cloud forests dissipate. The trees grow larger and thicker. The moss disappears from the branches and recedes to dark nooks and crannies. The air is no longer heavy with fog and moisture. One can see the sun peeking in through the canopy, drying the ground and withering the ferns and fauna. The mountains inland are colder and dryer. There is far less humidity, especially as one nears The World’s Grave. Instead of tall grasses, the foothills are covered in boulders and craggy rocks jutting from dry dirt and dusty gravel. Great forests spring up at around three and a half thousand feet. Unlike the spindly trees within the eastern cloud forests, the forests here are known for their astonishing size and bulk, with trees averaging two hundred feet in height. Their trunks reach a staggering fifty feet across. These forests, although less diverse than their eastern counterparts, are far larger and make up the majority of flora within the central part of the range. They cover the range like a blanket, crammed into small corners between mountains, marching up over the tops of the smaller peaks, and weaving between the enormous boulders and rocky crests that dominate the terrain higher in the range. The forests are beautiful. Their canopies strike out against the slate gray rock of the Skirhem. Within its heart, one can walk within shade for miles and miles, protected by the vaulted ceiling of the woods. Old rambling footpaths wind between ancient trunks, sometimes worn by fire and lightning, but alive nonetheless. These paths stretch for miles and miles across the range, most tapering off somewhere deep within, some leading back to the base of the mountains, only a few ever find their end at a village or hamlet. The Skirhem’s tallest peaks can be found at this part of the range as well. At six thousand feet, the forests thin, giving way to cold gray crests and treacherous cliffs. Not much grows here. Dirt mixes with gravel and shards of rock. Even farther up, at ten thousand feet, the mountains become far more dangerous. Here, snow and ice blanket the rocky terrain year round. Heavy cornices make avalanches an inevitability, eventually collapsing into rushing torrents of snow. From the trade routes skirting the desert below, many merchants and travelers have watched what seemed like entire mountain sides collapsing, flowing into chasms and off cliffs until they slipped out of sight. At its highest point, the Skirhem reaches fifteen thousand three and hundred fifty two feet. This peak is The Arcogas ag Skirhem, the tallest mountain in the range. This mountain pierces the clouds with sharp rock and icy minarets along its length. Its location deeper in the range allows for more precipitation, leading to the creation of giant glaciers that fill the surrounding valleys. Local legends believe that at its peak, an old Archon still lives, watching the humans below. If one should reach the old one, they shall be gifted a flawless axe that would never break. Some have attempted the ascent. None have survived.

“Old rambling footpaths wind between ancient trunks, worn by fire and lightning, but alive nonetheless.”

Southwestern Skirhem

To the west, the Skirhem tapers off. Mountains become blunt and lower in altitude until they are little more than foothills. The great swaths of forest thrive here, where there is no ice to stunt their growth and the air is rich with moisture once more. With such proximity to Viremar, the grass grows thicker and taller on these hills than anywhere else in the range. The soil, now rich and fertile, cushions one’s every step. The sun’s gentle heat seeps through the trees and warms the air. These woods, although not as tall as their mountainous brethren, hold more life and are far gentler. Ferns peek out from beneath the trees, shrubs and berry bushes thrive around the edges of the woods, where the grass is not as thick, and the sunshine is plentiful. This area hosts many that rush down, burbling under fallen trees and splashing over small boulders. They run down into the Verrdnam, a large lake nestled between the range and Viremar. Based in the flats of the southwestern border, the Verrdnam is the largest of a series of lakes and ponds that surround the western end of the Skirhem. Here, the runoff from glaciers far above collects in the lowlands, forming swamps and bodies of water. This vast lake hosts more than a few small villages along its edges. Being the closest part of the range to Viremar, these villages experience much of the same weather as Kirgas and Viremar proper. Here and there, shoots of Kirstemm grow, dwarfing most other vegetation. The air is heavy with moisture, and the squelching of mud is ubiquitous throughout. Chief amongst the towns encircling the Verrdnam is Verrdgas, the most prosperous fishing village of the five that surround the lake. It boasts the largest wharfs and piers and, with its ideal position on the northern side of the lake, trades directly with Viremar as well as the neighboring provinces. On the west end, there are Haever, Verrdhaf, and Meegrassh. To the east is Augrassh.

“Chief amongst the towns encircling the Verrdnam is Verrdgas, the most prosperous fishing village of the five that surround the lake.”